How to be an Author

About 100,00 British authors are published every year, and they all long for their publishers to pay for a publicity tour.

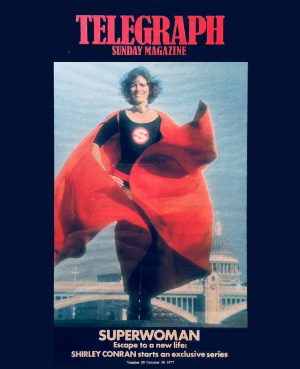

Many moons ago I wrote a book about how to minimize housework. When SUPERWOMAN was published, my publishers were a tiny Dickensian outfit in a Bloomsbury attic, and they hadn’t had a bestseller since before the first World War, when it was poet Rupert Brooke: they had little money to spare for publicity.

On the Sunday after publication, the publisher woke me at 7am and said in a disbelieving voice, “You’re number one. You’ve beaten Wisden!”

“Who’s he?”

“Wisden’s Cricket Annual. Now you must go on a publicity tour.”

I agreed to provide my new Citroen estate car, so long as the publisher insured it and paid for a driver.

I spent most of my payment-upon-publication on clothes for this tour – items that might be worn by a country bookshop customer – tweedy skirts and jackets. I was advised to buy something flashy for Glasgow, so I got an uncomfortable, scarlet velvet, mermaid-clingy dress with a low neck-line.

The Tour

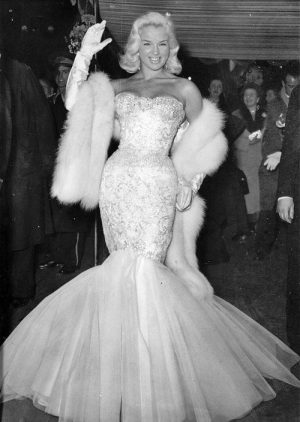

Cut to tweedy me, signing books for an appreciative small crowd at the back of a bookshop, when there’s a commotion at the front. My entire small crowd speeds off like lemmings. Blonde film star, Diana Dors has appeared to publicise her autobiography; she is wearing – at tea time – a white, satin topless gown and her shoulders are shrouded in white fox fur. I realised that booklovers do not want to meet an author dressed like a bookworm, but one dressed like a Christmas tree.

My next publicity stop was for TV in Glasgow and, as we sped northward, I realised that my driver was the worst driver on the planet. The red velvet dress was a success on TV but afterwards we found that my suitcase had been stolen from the unlocked – so uninsured — boot of my now-battered car. Goodbye all new clothes.

Red velvet for breakfast

My media schedule was crammed as full as a baby’s first Christmas stocking – TV studios, radio stations, local newspaper office and functions such as the Yorkshire Literary Luncheon. There was no time to stop ‘n shop, so I wore the red velvet for twelve days from breakfast TV to bedtime, and I grew to hate it.

One wet and windy night on the way to Norwich, the chauffeur smashed my new car, the last in a six-car pile-up. My driver had forgotten to insure the car. My first publicity tour cost more than the revenue from sales that it was supposed to promote.

Towards the end of this tour, I was joined by former Prime Minister Edward Heath, who had just knocked me into 2nd place on the best-seller list with his first book on sailing. At every bookshop, blue-rinsed matrons and decent chaps in cricket blazers queued round the block to purchase Ted’s book. He had to organize a production line: one clean-cut chap would take the money, a second one would thrust the opened book in front of Ted, who barely had the time to scribble his signature before a third young man snatched it away, to make room for the next one.

Meanwhile at the next table, to avoid humiliation, I signed books for my little groups as slowly as possible, with personal dedications and long messages (“Tell me more about your aunt.”)

Together, Ted and I also attended glittery events, such as the Yorkshire Literary Luncheon. After my first speech, Ted looked a bit worried and coached me. We remained friends until he died, 30 years later. This man, who could seem huffy, had the rare gift of friendship, and at his big parties, as he approached, faces softened into smiles and eyes shone with love. Whenever I asked his advice, Ted’s reply was always good advice, whether it was about finance or the correct action to take when waiters don’t take any notice of you.